Since I've been asked a couple of times - and apparently quoted as an example - I figured that it might make sense to put some words on paper on this one. Note that this technique is not my invention, but it is an adaptation to horror gaming from a little-known game called "Puppetland" by John Tynes (rules freely available from the internets).

One of the key ingredients in horror genre is stress. Usually this comes from powerful visual imagery or - in the case of gaming - the players own imagination as they visualize the horrors that their characters encounter. Or it can be more subtle and come from collapsing relationships or watching someone you love destroy themselves. However, it's a bit difficult to get yourself into the horror genre when one player is hunting for Cheetos and another one is reading a rulebook. Focus is very important.

Deadlines tend to focus people very efficiently. They also generate loads of stress, as anyone who has to live by a calendar knows. So I figured that it's worth a shot: introducing artificial deadlines into gaming should introduce stress and focus into the game, even though it is not a horror element as such. As players are very good at suspending disbelief when it comes to imagining that dice can represent monsters, surely it would be easy to believe that one kind of stress is actually some other kind of stress?

Turns out this theory works wonderfully. So I'm running a Call of Cthulhu game, in which each game is limited by a chess clock to a period of maybe 35 minutes at its shortest to 1h 30min at its longest. I set the clock to a shorter time if the scenario is straight-forward and needs lots of action; if I want to get a darker, threatening but slower game, I give the clock a bit more time. There is an in-game device which does tell the characters the time as well, and it's fairly easy to explain as an "alien device which tells how much time there is left before the portal closes, but sometimes it runs faster and sometimes it runs slower and you don't really know when and how." If they players say "we fly to Paris", then the clock runs really slow; if they enter combat, the minutes drain very fast. But I am unsure whether you would really require that kind of an in-game device at all. Do try and tell me.

Of course, since the clock does not stop for anything it means that the GM needs to be very knowledgeable of the game as well. There just isn't time to go leafing through the sourcebooks: everything has to come out in a snap. I joke that in this game, writing a scenario takes longer than playing it. But the increased intensity of the situation is well worth it; it's very rewarding for the game master to get swept away by the emotion flowing from the players.

And buy, is there emotion. I am not sure as I was rather immersed in the game myself too, but I think I saw a player jump to his feet in excitement last time we played. And you can hear the creeping terror in their voices, as they try to figure out exactly how to keep a gigantic fluid creature in a barred cage (answer: there is no way) with 15 minutes left on the clock and the friendly receptionist they tied to a table so that she would be safe is going to be EATEN ALIVE by a thing that crawls on the floor and ululates in a terrible, forgotten language and they possibly don't have time to do everything they NEED to do and they simply have to choose who to save...

For a middle-aged guy with a family, gaming with a clock does bring in other benefits as well: games have a well-defined length, which means that they're easier to plan for. They're also easy to play as fillers or when all people can't make it - since the sceneario ends by clock, there's never a case where the scenario gets "adjourned in a suitable place so that we can continue later on". It does not preclude long campaigns, but it does require certain advance planning, since the players will not spend time digging up all the clues.

Obviously, this wouldn't work for everyone and for every campaign, but I was surprised to see how well it worked for us. Instead of a book, think of a TV series: 42 minutes, and that has to be the whole story. Think Pecha Kucha: you have time to tell maybe one or two things, and then it's over.

And hey, if it's boring, at least it's over fast. ;-)

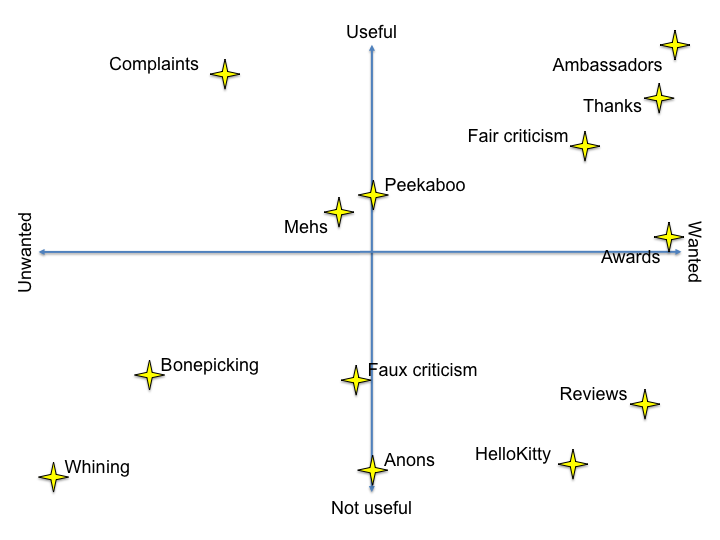

There's positive feedback and there's negative feedback. The old rule is that you should also try to be constructive in your feedback, so that's clearly a third kind. However, there's still a lot more than just those tree, so here's a list of some of the different kinds I've met over the years.

|

- Whining. This is the lowest form of feedback, because it mostly just concentrates on why the complainers life is useless without such-and-such feature, and often also includes predictions of doom.

- HelloKitty. OMG LOL LOV UR SITE KTHXBYE. Probably positive, but one can never be too sure. Also known as "fly-by thanks."

- Complaints. People who have a genuine problem and have gone through the effort of actually filing a complaint. While they can be annoying, the concerns they do raise are genuine and can really make a positive impact on your product. After all, they care about your stuff. Can become good allies, even ambassadors.

- Reviews. These are an old-fashioned and not always very relevant form of feedback. Since they come conceptually from old media, they usually are not changed after publishing, and therefore work only for products which are changed rarely. For a modern web site which are updated sometimes several times a day, they are obsoleted quickly.

- Bonepicking. No matter what you do, some people have a bone to pick with you or your company, and will take everything that you do in negative light. Slips easily into whining, but can be a genuine complaint too.

- Awards. Awesome stuff, if given genuinely.

- Ambassadors. Folks that are so into your product that they go out and spread the word. Treat these people well, for their feedback carries extra weight.

- Faux criticism. This is usually just cloaked whining. It appears on the surface to be useful, but often turns out to be a complete failure to understand what the product is supposed to be doing and applying it to a focus group of one. ("My cell phone does not whip cream very well. I think there's a big portion of people in the world who would like to whip cream with their phones. If you cannot bring such a product to market, you will lose all those people.")

- Fair criticism. This is the kind of stuff that one should really grip when it comes in. It doesn't mean that you should do what it says, but at least you should understand where it comes from, and preferably respond kindly.

- Mehs. "Yeah, it's kinda okay." This is a good warning sign that your product isn't rocking the boat, but as for its informational value it's pretty much zero.

- Anons. Anonymous/pseudonymous commentary on web sites. This is almost like noise, and going through it is usually as useful as peeling your skin with sandpaper. Yeah, it does exfoliate, but it's painful and you could spend the time more wisely.

- Peekaboo. Comes in, gives you an incomplete bug report, and then completely disappears or is unable to give any more information. Often does not have very good language skills.

- Thanks. Just simple, heartfelt thanks. While they may not make your product better, they do make you feel better, and that's really why you do what you do, don't you?

Private comments? Drop me an email. Or complain in a nearby pub - that'll help.

|

More info...

|

| "Main" last changed on 10-Aug-2015 21:44:03 EEST by JanneJalkanen. |