In 1957, one of the greats of science fiction, Isaac Asimov, wrote one of his famous robot books: The Naked Sun. He describes a world called Solaria, where only 20,000 humans live alone on vast estates, with every need catered to by a billion robots. They, of course, have a vibrant social life, but only by “viewing,” that is, telepresence. “Seeing” other people physically is frowned upon so much that people feel nauseated if another living person is in the same room. (Then a murder occurs, and a detective is sent to investigate from planet Earth – a planet with billions of inhabitants, where privacy is rare and underground city streets are constantly crowded with millions. The Solarians are naturally distraught, and this drives a lot of tension in the book. It’s a great book; you should read it!)

Why dig old speculative fiction? First, I like it. Second, sci-fi writers make their living by thinking very hard about the future, but without a lot of pressure to be “sensible” in whatever way “sensible” is defined in their times.

And third: You can be very sure that the current tech leaders have read the same books. Some of them are actively trying to bring some of them to life.

What got me thinking about this book was some of the weak (and not so weak) signals that I’ve been seeing recently.

We are losing the human connection

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, remote work was on the rise. The freedom to work any time from anywhere was holding great promise to certain expert jobs, but COVID-19 really broke the bank, and many people found out the hard way that yes, their jobs could also be done remotely.

And I get why people like remote work: commuting is terrible and skipping it frees hours of your time per day. Working remotely means you can also find more affordable housing away from the city. There are clear productivity gains for certain tasks when you are basically in focus mode most of the time and don’t have to suffer constant interruptions. For the more introverted people, remote work can be a great anxiety management system.

Also, while we are right now seeing AI replacing white-collar entry-level jobs, we’re also seeing the first steps of human-like robots stepping into the areas traditionally thought of as blue-collar jobs such as factory-floor work. It is obviously a huge disruption when a programmable, mass-producible tool can be used to replace workers in entire industries. It has happened before, and we remember those times as the First and Second Industrial Revolutions.

At the extreme, we see the *otaku*, people who like to isolate in their own homes and not have any physical social interactions. Everything is ordered online, including social life.

A not-so-extreme example is how people in Western countries are turning inwards, something that the Harvard Kennedy School calls the “Friendship Recession”. People spend more time at home and less time seeing friends. The so-called Male Loneliness Epidemic (which is more likely an “everybody loneliness epidemic”) is just one aspect of this.

Return of the teenage bedroom

This is honestly a bit of a weak pet theory of mine, so you are free to ignore this chapter, but hear me out: A massive portion of the internet innovation happens because the young founders, barely out of college or university, desire to go back to the happiest period of their lives — the teenage bedroom. Dad drove you around? Uber. Mum made you food? DoorDash. Endless entertainment? Netflix. Hanging with friends around the mall? TikTok. Dreams of the conquest of space? SpaceX.

Many of the corporate founders are people who had only very limited experience of life when they started. They locked in a particular kind of culture, and the stereotypical CEO self-searching and experience hunting cannot really change the culture already established.

I like this hypothesis as it sort of kind of explains in my mind why we don’t seem to evolve as a society that much. Yes, tech evolves, but the big and massive societal changes seem to revolve around the comfort of the middle-class teenage bedroom from the 1990s.

The rise of the social algorithm

There is also a big social experiment running — the regular human contact is being mediated, perhaps even replaced, by social algorithms. You no longer just meet people because you happen to share the same job, hobby or local pub; no, you see content from people that the algorithm deems suitable for you. An algorithm that’s optimized to maximize your engagement with the site itself, not with the people. Sometimes it’s as simple as listing the latest content – the Fediverse is the linear-TV equivalent of social media – but the smartest algorithms are self-learning and very good at wasting your time. Time, of which you have a limited supply.

But the big thing is *scale*. Internet companies are built around scale: they need to grow their revenue constantly. Some economists argue that in service industries, there is no limit to growth, but most firms battle for eyeballs and user time, both of which are limited resources.

Frictionless wins

One key thing in the online battle is the idea that frictionless wins. The company that builds a service that needs less interaction, less learning, less commitment and less money from the user is more likely to win the fight.

The problem is that online is almost always less friction than physical. It’s easier to order stuff online than walk to the store. The assortment is always better. The prices often cheaper too, if you don’t mind waiting an extra day. In Finland, robots deliver your groceries so you don’t have even the social friction of meeting a human.

The need for growth automatically drives internet companies to less friction by reducing the physical activities of customers and moving towards online. Meeting people is a hassle. Calling them is less of a hassle. Messaging them is even less of a hassle. Watching a TikTok stream is even less, since you don’t really have to do anything; not even swipe.

Frictionless scales.

Growth needs scale.

Therefore, the internet companies (well, any company really, but the internet companies are at the forefront) are compelled to drive *solarification* of the world. We simply need to be isolated and pampered by robots, because it’s the only way towards a truly frictionless world.

Roll “save vs limitless growth”

Of course, this is hyperbole. My desire is just to highlight that there is a logical end result for the growth needs of the internet companies, and call for more human technology.

Still, there is delicious irony in looking at internet CEOs railing against remote work, yet trying to make sure their users never have to meet a living human. Return-to-office does not make work have less friction, on the contrary! Work life is stressful, and with our population aging with less people supporting the economy, it’s likely to become even more so.

There is also growing awareness of the mental and physical toll that isolation and stress takes on you. People who work from home might move less (there seems to be conflicting research on this), and anxiety appears to be increasing on the whole.

Also, bluntly put, there are limits to growth. The “Limits to Growth” model from the Club of Rome, and its updated versions, does set some hard limits on how much growth can be achieved. But if you think about it this way: 20,000 people would not be a big burden on Earth, no matter how advanced a lifestyle they lead. So perhaps there is a callous movement out there as well, people who plan to be the progenitors of those 20,000.

So what?

A very good question indeed, my friend! I’m sure some of my readers are right now thinking that hey, that does not sound so bad, actually. Living in a utopia, where you don’t have to meet dumb people, and all your needs, wishes and fantasies are catered to by intelligent robots.

For others, this would be an absolute dystopia. Not being able to meet and feel other people? Spending your entire life in a high-tech version of Teams? Horror.

And, for engineers, you have to think about the brittleness of such a system: Is there enough genetic variance? Could power be grabbed and society be disrupted by bad actors? How about global tech malfunctions or natural catastrophes? Could society survive with such low numbers of people? What would happen to culture? Would they entertain themselves with an infinite number of old TV reruns and an unlimited stream of jabbering in Teams meetings? Would it be a monoculture, and we would lose all historical context of the thousands of cultures enriching humanity right now?

Could such a society *evolve* in any direction, or would it be a stagnant endpoint?

|

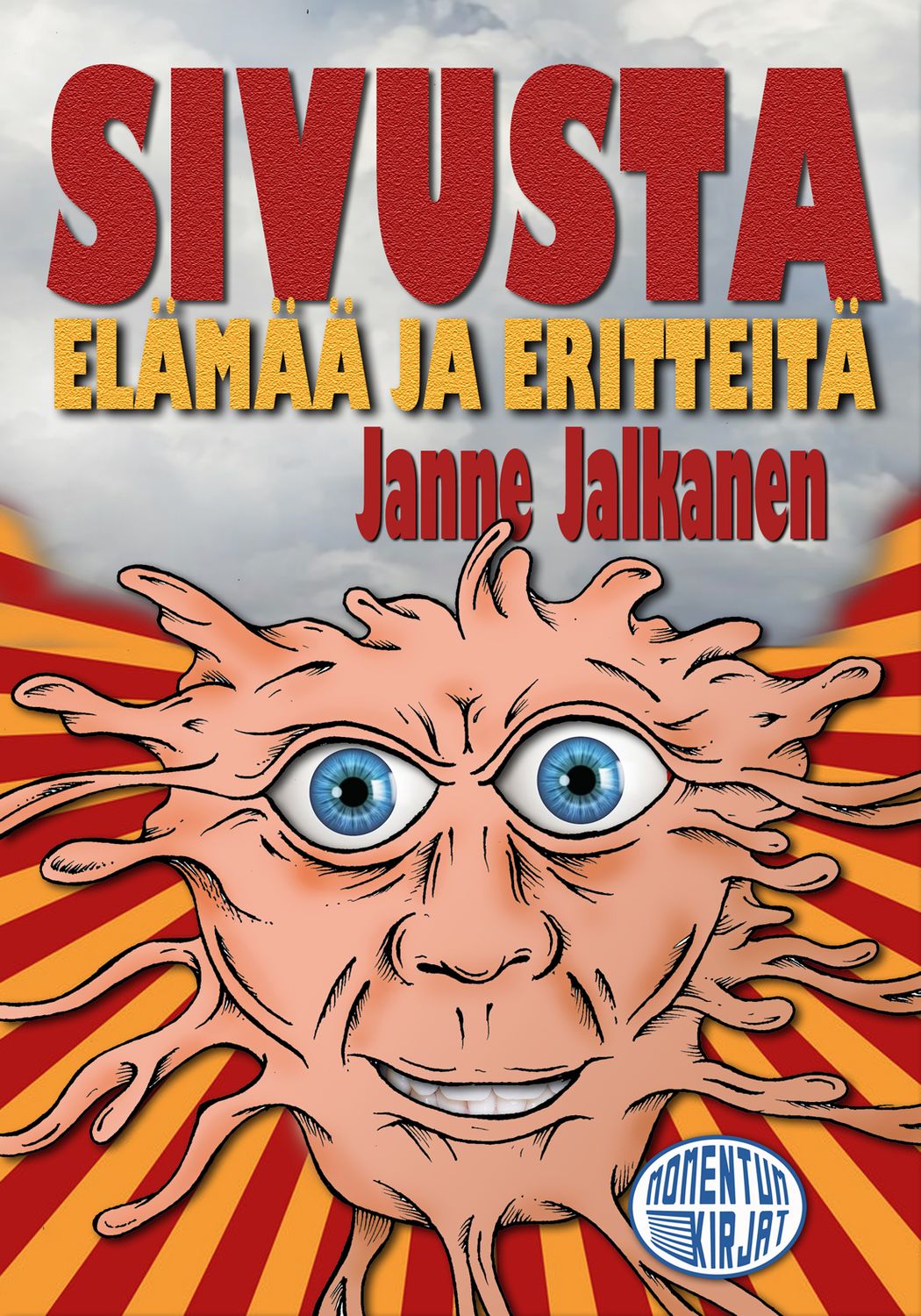

Sivusta, tuo maanmainio oravien pitämä blogi/rukousmylly, on siis saatavana syyskuusta alkaen kirjamuodossa! Tässä jonkinasteinen mainosteksti, joka on tarkkaan optimoitu hivelemään juuri SINUN ostohermojasi!

Minkä hyllyn tyhjentäisit kaupasta ensin maailmanlopun tullessa? Entä jos kuulisit, että oletkin oikeasti rovaniemeläinen taideopiskelija vuodelta 2032? Miksi aamuisin suussasi maistuu niin oudolta? Mitä on dementtisima ja kuka oli Eenokki? Ja kuka on maailman kuningas, edes hetken? Ja missä - oi, missä - on Kaaleppi?

Sivusta on kokoelma kertomuksia, lastuja ja runoja, jotka vaihtelevat empaattisesta epätoivoiseen, fiilistelystä filosofiseen ja reteästä raastavaan. Se on kirjallista jazzia, joka inspiroituu niin absurdin huumorin mestareista, muotiblogeista, kuin japanilaisesta haiga-tyylisuunnasta, jossa runoutta yhdistetään valokuvaan tai maalaukseen.

Sivustasta vastaa uukuniemeläinen sinappi-, silkki- ja sidontakonglomeraatti Sivusta Yhtymä, sen esoteerinen päätoimittaja Z, "asiakaspalvelun" Luigi, sekä muutama satunnainen orava.

Sivustaa kirjamuodossa voit tilata ainakin seuraavista asiantuntevista kirjakaupoista alkaen noin 20.9.2025!

- Momentum-kirjat (silleen kiva, että sillä lailla kustantaja saa eniten massia ja on tyytyväisin ja minä en saa piiskaa)

- Suomalainen kirjakauppa (joka luokittelee tämän runoudeksi, mutta se johtuu varmaan siitä, että heillä ei ole "häröpallo" -kategoriaa)

- Akateeminen kirjakauppa (mitään akateemistahan tässä kirjassa ei ole, paitsi että on tästä yksi opinnäytetyö tehty!)

- Prisma (josta et voi ennakkotilata, mutta sitten kun voit, niin saat bonukset! Bonukset! Booooonukset!)

I've used this analogy before, but I think of my social media feed as my living room. I decorate it how I want because I want to feel comfortable there. Maybe put a plant there, TV there, nice couch. Lots of books. Analoguously (is that a word?), I block and mute people on social media - even though I don't own the space, I still feel somewhat responsible for it and for the atmosphere there. Sometimes house parties are fun even when they're noisy, and people don't need to agree with me, but bad behavior gets you thrown out. Or not even let in.

This has been my guiding principle since my blogging days, and although I now, as a middle-aged white man, avoid the worst trolls, this approach has worked well for me and kept social media relatively well-behaved. To continue the analogy, I gave up on X years ago when it started to feel like the neighbourhood had become too rowdy and friends were moving away from the area too.

Another important guideline I've followed is trying to limit myself to three comments in any thread. If I can't express my message in three comments, the situation usually doesn't improve no matter how much I argue. Of course, this isn't a strict rule; especially on platforms with strict character limits, sometimes you need to write more. And sometimes the conversation is genuinely interesting and you learn something new. And sometimes the banter is just too fun 😎

Nevertheless, I've recently noticed myself becoming increasingly cautious about commenting - especially in other people's feeds. In Discord, WhatsApp, Facebook, and other closed environments, I might open up more and share my opinions - especially when asked - but publicly... the threshold has clearly gotten higher.

Part of the reason is surely the deconstructive nature of the internet: if your argument has even the slightest flaw (like a spelling error or a comma mistake), it invalidates your entire argument. Sometimes it feels like social media is one big malfunctioning computer, and if you feed it even a slightly flawed program, it spits back an enormous amount of error messages primarily aimed at insulting the programmer.

This is perhaps an unspoken dark side of meritocracy: putting down others' skills is just as valid a way to advance in the hierarchy as improving your own skills. And since meritocrats often view empathy as weakness, they don't see anything wrong with this approach. Even though it automatically excludes a large portion of humanity from their hierarchies and makes meritocracy automatically an activity for a small inner circle.

I won't start delving deeper into meritocracy and its problems; smarter people than me have surely written about them. I'm just highlighting this one aspect that I think plays a big role in social media.

I don't know how much of this stems from the internal and business logic of these social media systems, designed and funded by people living and breathing in the meritocracy, who perhaps can't even think in any other way. I'm too close to this myself that I might not even be able to imagine what the alternative would be. (And no, don't offer the Fediverse; if you do, you haven't quite understood my argument about meritocracy.)

But now that I've been observing social media for a quarter century, I have a strong feeling that there must be an alternative to this design. The basic feature of social media is that it's made by people, and the more people, the better it should be. Now it feels like there's a limit beyond which social media cannot scale without getting out of hand.

Small communities, like Discord servers, Reddit forums, and some FB groups, stay together precisely because they start from this "living room" thinking, where strong moderation keeps the discussion reasonable. But stupidity and greed (aka bots) scale faster than moderation capability.

Perhaps the most functional example of a large working community are wikis, like Wikipedia. They don't value "discussion" as inherently valuable, but as a means to reach an outcome.

I don't know. I have some ideas that could be worth trying. If only I had the time... but there's so much fun stuff to do in the world 😅

|

Silti tässä on kyllä jotain messiaanista.

Kamalaa sinällään sanoa, mutta pidän tästä kuvasta enemmän kuin monesta muusta AI-kuvasta, jota kuvavirrassa näkyy. Suurin osa AI-generoiduista kuvista on kuitenkin "AI-liejua", johon ei halua sen suuremmin sotkea itseään. Toki se johtuu siitä, että mediankulutustottumuksemme - loputon skrollaaminen - ohjaa siihen, että sitä kontsaa pitää olla myös loputtomasti, jolloin AI-liejulla ja tuhannennella kissameemillä ei ole paljoakaan enää eroa kuluttajalle. Naurahdus, klikkaus, ja scroll.

Niin kauan kuin ihmiset käyttävät aikaa skrollaamalla ja etsimällä jotain hetkellistä täytettä elämäänsä, niin järjestelmä optimoituu kohti halvinta ja helpointa tapaa tehdä sisältöä. Ja AI tekee sitä personoidusti ja loputtomasti. Ei vielä halvimmasti eikä hyvin, mutta se on vain teknistä optimointia. "Hyvä" tarkoittaa somen tapauksessa "eniten klikkejä ja tykkäyksiä". Olemmehan optimoineet interaktionkin niin vähäiseksi, että tietokonekin osaa.

Onko mulla jokin pointti? Ehkä. AI-lieju menee sinne minne ihmisetkin, niin kauan kuin malli on loputon skrollaus. Siltä ei pelasta fediversekään. Mutta jos voimme muuttaa interaktion internetin kanssa sellaiseksi kuin mitä interaktio on ihmisten kanssa (eikä päinvastoin), niin ehkä se vielä pelastuisi. Siinä AI:lla voi olla hyvinkin paikkansa; ei sisällöntuottajana vaan keskustelukumppanina.

Clauden oma kommentti tähän kuvaan ihan vain näin loppukaneetiksi: "The final result achieves both the aesthetic beauty and meaningful commentary I was hoping for. It's a hopeful vision of how technology might integrate with nature in ways that preserve and enhance both realms. The visual storytelling is subtle yet profound - showing technology as a caretaker and partner to nature rather than its replacement."

Kävin pelaamassa tennistä ja törmäsin tuttuun. Mainitsin sitten että tuli nuorena pelattua enemmänkin, mutta niistä ajoista on kymmeniä vuosia jo, mutta yllättävän helpolta on pelaaminen tuntunut näinkin pitkän tauon jälkeen.

Lihasmuisti diipa daapa joo, mutta aloin miettiä, että onko tässä ehkä enemmän kyse siitä, että vielä muistaa, miltä hyvä näyttää ja miltä se tuntuu?

Mutta - Linkedin-hengessä - tätä ajatusta voi soveltaa moneen muuhunkin, kuten yritysmaailmaan. Kun menet ensimmäiseen työpaikkaasi, sinulla ei luultavasti ole käsitystä siitä, miltä hyvä näyttää. Millainen on hyvä työpaikka? Millaiset ovat hyviä käytäntöjä? Millainen tiimirakenne on hyvä? Sitä vaan roiskii menemään muiden seassa, joista kukaan muukaan ei ehkä tiedä, miltä hyvä näyttää. Silloin kaikki keksivät pyörää vain uudestaan ja uudestaan. Etenkin startupeissa löytyy kaikenlaista sekoilua ihan siksi, että nuoret puuhastelevat keskenään ja cargokulttaavat menestyneitä teknologiajättejä oikeastaan ymmärtämättä, miksi.

Mutta sellaiset, jotka päätyvät jo heti nuorena työpaikkaan, jossa on panostettu hyviin asioihin (mitä ne nyt sitten ovatkaan kullakin ammattialalla), niin kaikissa seuraavissa työpaikoissa on helpompi paimentaa asioita parempaan.

(Ja en siis tarkoita, että jotain tekniikoita tai menetelmiä pitäisi kopioida, koska ne eivät välttämättä siirry yritysten välillä. Tarkoitan ennemminkin sitä epämääräistä fiilistä, kun hommat hoituu, arki rullaa, ihmiset on kivoja, asioita saadaan aikaan ja tuntuu siltä, että tekee jotain merkityksellistä ja oikein, tiedättehän?)

Ihmissuhteissa sama juttu: jos sinua on koskaan kunnioitettu, rakastettu, annettu tilaa ja oltu kumppanina ylä- ja alamäissä, niin osaat myös vaatia näitä tulevilta suhteilta.

Kokemus suojaa huonoilta valinnoilta, etkä voi parantaa asioita, jos et tiedä mitä parempi tarkoittaa.

Siksi olisi itse asiassa hirveän tärkeää, että yritykset, joissa hommat toimii, ottaisivat sisään nuorempia ja päästäisivät heitä myös pois sopivan ajan jälkeen. Ihan näin kansallisis-kilpailullisistakin syistä, kun ei meillä hirveästi ole varaa huonoihin yrityksiin, jotka hukkaavat ihmisten lahjakkuutta kaikenlaiseen turhaan vitutukseen.

Private comments? Drop me an email. Or complain in a nearby pub - that'll help.

|

More info...

|

| "Main" last changed on 10-Aug-2015 21:44:03 EEST by JanneJalkanen. |